Excerpt from a lecture about Participatory practice in Anandshala (An out of school educational initiative with Laman Banjara community in Osmanabad district):

For 5-7th graders we used – Quest’s सक्षम बनूया Marathi and Math series specifically created for students in 5-7th grade who are not at their grade level. There are 3 workbooks each for Marathi and Math. The series came with a baseline test that was supposed to place students at the 3 levels. At first glance the tests looked like they might need localisation or at least simplification of language.

For example, the long prompts in the Math test were difficult to read. र ट फ करून वाचताना प्रश्न काय होता ते मुलांना विसरायला होईल अस वाटलं. भाषा थोडि सोपी करायच काम मी केल आणि मग tests घेऊन तीन तांड्यामद्धे गेलो. ह्या तांडयामध्ये मागच्या वर्षी पासून काम चालू होतं, त्यामुळे facilitators ना मुलांचा अंदाज होता. 2 facilitator ना test ठीक आहेत अस वाटल. गणिती भाषा मुलांना यायलाच पाहिजे त्यामुळे भाषा बदलू नये अस त्यांच म्हणण पडल. दोघेही डी एड झालेले त्यामुळे शिक्षक, शिकवणं, टेस्ट याकडे बघण्याचा दृष्टीकोण थोडा फिक्स झालेला. तिसरा तांडा थोडासा इतरांपेक्षा मागे पडलेला आणि नुकताच कॉलेज ला जाणारा facilitator. त्याच्या मुलांना भाषा जड जाईल अस त्याला वाटल.

मग आपण नक्की काय टेस्ट करतो आहे यावर चर्चा झाली. गणित करता येतं का मराठी वाचता येत याची परीक्षा होणार आहे असा उलट सुलट विचार झाला. सर्व प्रश्न गोरमाटी मध्ये translate करायचा प्रयत्न चालू झाला. पुनः थांबून खरंच हे पूर्ण गोरमटी पाहिजे का? मुलांना देवनागरी मध्ये लिहिलेल गोरमटीत वाचता येईल का असा ऊहापोह झाला. मग एक 8 वीतला मुलगा तिथून जात होता त्याला बोलावल आणि विचारल – तुझ्या 5-7 वी तल्या मित्रांना हा पेपर दिला तर यातल कुठे अडेल?

Instead of taking standardised test as they were we started asking the question ‘what do we want to know?’, when we got stuck at localizing the tests we looked for ‘local experts’, rethinking ‘who knows what we want to know’ instead of going to the obvious options of trained teachers from the community. We found diverse voices.

When conducting the baseline evaluation, instead of a timed test we decided to give the students as much time as they needed. The test was portrayed as a mirror for themselves. A tool that will tell them where they need help and ask for it from the facilitators. Instead of worrying about standardized scores we gave importance to maintaining student’s confidence while getting the information we want to place them at the appropriate level.

In the math test the facilitators explained the questions in Gormati if somebody asked for it. If a student couldn’t read fast enough to understand the question, we read it out to them without any further explanation. Timed tests make sure that the student is fluent, so to understand the level of fluency we marked the time the test was returned. The score and the time were used together to understand the student’s skillset.

The testscores were aggregated for each student as well as for a Tanda for each question or set of questions. This gave us a general idea of where the group stood in terms of skills. For example, 50% of students in X tanda cannot do multiplications. 80% can do addition, subtraction but only 70% can do हच्याची वजाबाकी. So the facilitators got a more actionable input about their students about specific areas, rather than a score.

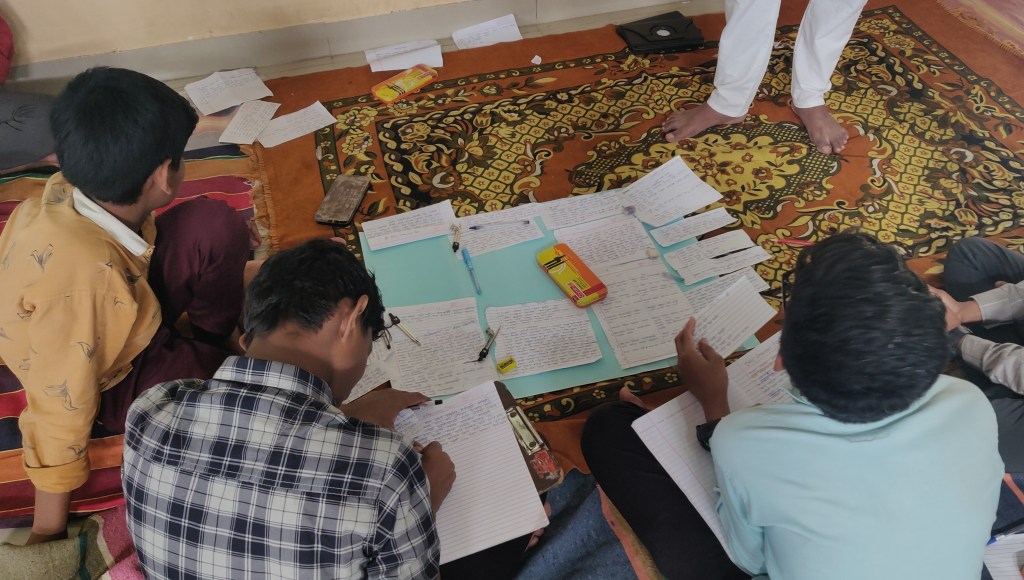

We had decided to start from the 1st book in the series. The scores were used to divide students into 3 groups green, pink, and blue according to their ability. The idea was that blue group would be able to go through the workbook on their own. दृढिकरण was the purpose. The pink was the middle section, the instruction, speed was planned keeping them in mind. The hirva needed more attention. The facilitator could do that when the gulabi group was solving their workbook as well as ask nila group students to help-out if they were stuck. Given the environment of the classroom, students felt at ease to help their peers. Rather it was encouraged, in contrast to the individual focused tests and activities in school.

Initially I provided the list of students for each group, and explained how I arrived at it. The facilitators later adjusted by moving some students between the groups when they realized they were getting stuck or were faster than expected. They also felt confident enough to assign a new student to a group, observe and move them to the appropriate group. The weekly facilitator meeting was a place to discuss such tweaks.

The collective reflection was an important aspect of the success of this phase. In addition to observing their students and their own practice, the deliberations of these observations helped some reflect on their beliefs and assumptions. For example, an interesting conversation among two facilitators verbalised their cognitive dissonance about हुशार कोण. Surprised at seeing names of some of their students in the Green group, the group of students that were lagging the most:

“They write so well. It is clean and beautiful.”, said Sunita

“I felt the same way when I got my list, but if you see their test papers, you can see they couldn’t do it.” Pranita responded.

“Let’s see, said Sunita, When they start with the workbook I can move them if needed”

There was an epiphany that, beautiful handwriting does not mean the student comprehends what they are reading or writing. Writing can be just like copying a drawing.

Not everybody started with questioning the lists. Initially, it was considered as given. Highlighting my position of power as an educationist, the primacy of tests and numbers over the facilitators’ knowledge of their students. However, in 2-3 weeks, most were able to judge ability of newly arriving students without a baseline test and moved students between groups as they progressed at a slower or faster pace than others. By the midterm in October and the post-test at the end of the year, facilitators had a better understanding of what their students can and cannot do, where they trip when solving math problems or completing language tasks in the workbook. The trust in the tests was still intact but there was more openness to question the things that did not work.