My first exposure to Vijaywada and the language environment of my new home was a conversation with the uber driver. We interacted with help of our mixed repertoire of English and Telugu. I do not speak Telugu (yet). He taught me some useful everyday terms. I told him about Telugu I have heard in Hyderabad. Then the conversation moved to the different Telugu s. The Vijayawada Telugu is the pure Telugu he said and then proceeded to explain the differences with other regional versions with everyday examples. The forms of verbs, the intonations, some words that differ.

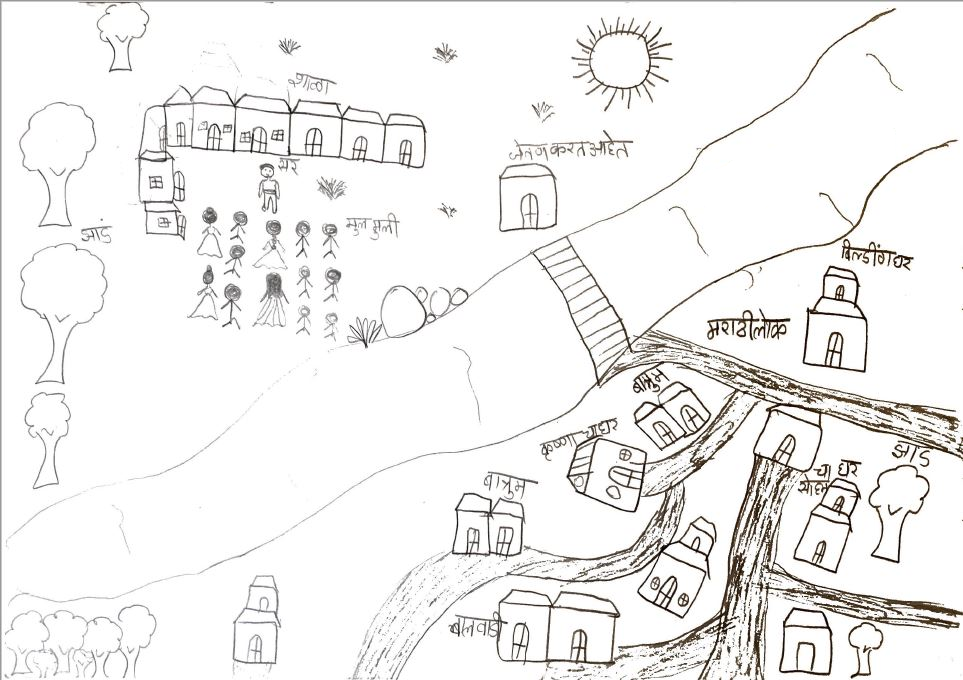

That conversation stayed with me because it made me think about a similar possible conversation with a Puneri person. Many times Marathi Praman Bhasha is equated with the formal register. However, there is an added layer of regional hierarchy. The Puneri Marathi and its formal register are Praman. The formal register of the languages in other regions are still not up to the mark.

When I refer to formal register I am talking about language spoken at formal occasions rather than everyday speech. Formal does not mean pure. It only means situational. Other registers could be spoken vs. written. Then there is the difference between written to friends, colleagues, boss, vs government/official/legal notes.

These registers are just the way we speak/express depending on where we are and who we are speaking to. It is not about correct or incorrect language. The problem starts when we see it as a hierarchy and treat one register as ‘proper’ or shuddh शुद्ध (pure) language. In doing so we have forgotten the regionality of the Puneri Marathi register.

If Praman Bhasha were truly neutral, who would feel most at home in it—and who would feel most exposed? Puneri Marathi quietly standing in as neutral or pure or the original untainted marathi, makes distinctions between registers not just functional. They are moralised. Speaking or writing differently is no longer just “informal” — it becomes “lazy”, “incorrect”, or “uncultured”.

Thus when a child, a teacher, or a community speaker is told their Marathi is ashuddh अशुद्ध, what is really being corrected is not grammar but location, physical and social.

Related Reading:

All the Englishes by Akshaya Saxena: She talks about helping students in her literature class question “how language itself shapes our ideas about ownership and belonging” with the help of Amy Tan’s essay ‘Mother tongue’.